Dr. Margaret Hillenbrand (University of Oxford) wrote article Remaking Tank Man, in China (Journal of Visual Culture) discussing extensively on Lily Honglei’s augmented reality work Tiananmen Squared and animation Forbidden City. Read excerpt below:

This notion of digital questing, and via camera-based platforms, steps up a notch in a recent work by the anonymous artistic collective 4Gentlemen (a pseudonym used by the Lily and Honglei art studio). Entitled Tian’anmen Squared, it uses the smartphone technologies of augmented reality to allow Tank Man’s spirit to return to Beijing and stalk his former haunts (4Gentlemen, 2011). More commonly associated with military or gaming applications, augmented reality has shaped up in the last few years as a potent tool for conceptual artists. Its highwater mark so far is probably Amir Badaran’s Frenchising Mona Lisa, an app which allows users to train their phones on any version of Da Vinci’s painting and watch as the enigmatic one miraculously removes her feather-light veil and wraps the Tricolore around her head as if it were a hijab. French secularism, sartorial hypocrisy (why are some scarves ok and others not?), curatorial control, the whims of iconography, and the shifting status of the artist all coalesce as targets within the frame here. Criticized by some as a self-promoting prankster, Badaranargues for the value of augmented reality as a ‘legitimate installation art medium’ (Hube, 2014). He seeks, as he puts it, to ‘bring AR-as-art into the museum’ (Hube, 2014) and his abiding gripe is, indeed, with the Louvre as a stuffily sacrosanct institution which he debunks via invasionary attacks, essentially breaking into the museum to make his mischief. These notions of appropriate space-use, and how to violate it, have been crucial to augmented reality as an art form, as interventionist installations such as Sander Veenhof and Mark Skwarek’s 2010 AR exhibition in MoMA showed very clearly. Over 30 artists took part in the ‘art invasion’ exhibition, showing their works all over the building and effectively annexing the museum space for any visitor who had the app installed.

Needless to say, this idea of spatial pranking has broader implications. Some of these have been mapped, quite literally, by 4Gentlemen, who have used the AR application Layar to invade the space of Tian’anmen Square and its surrounds with verboten memories. Once downloaded onto a smartphone, the app uses geolocation software to superimpose a computer-generated icon of Tank Man, sized to the original scale, at the exact GPS co-ordinates on Chang’an Avenue just off the square in Beijing where the face-off between man and machine took place. In keeping with the photographic nature of this enterprise, the app also allows users to take pictures of the scene in the viewfinder, with the Tank Man icon overlaid. On one level, then, the Tian’anmen Squared project shares space with the work of Baradan, Veenhof, and Skwarek, infiltrating consecrated ground with below-theradar visual messaging – but with a sharper twist. Tian’anmen Squared is not simply iconoclastic (Frenchising Mona Lisa) and anti-establishment (squatting in MoMA); it does not merely work on or alongside existing canonical works. Its impulse is also recuperative, since it reinstates at the original flashpoint of its occurrence a virtual icon of memory which state censorship has attempted to wipe from the public ‘hard drive’. Tank Man – the wraith, the disappeared, the deleted – thus stages a defiant return to the square, commandeered back from US liberalist discourse and installed once more in the highly localized site of his political agency, while also mimicking, through his hidden presence in the open air of central Beijing, the very machinations of the public secret.

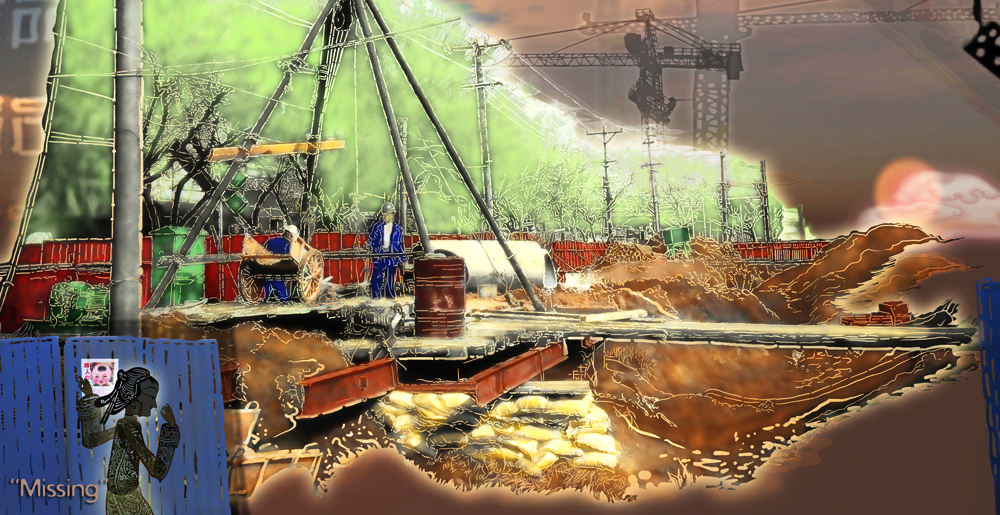

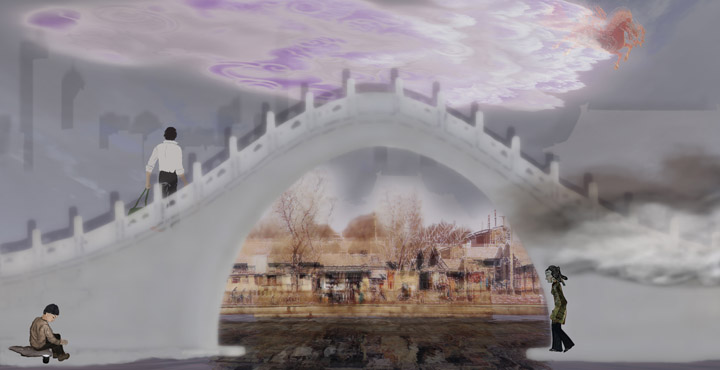

Like most AR technologies, Tian’anmen Squared merges public space with sudden and clandestine computer-generated icons, but here publicness is both more municipal and more prosaic than in Franchising Mona Lisa, which takes the rarified air of the Louvre as its stage. Tian’anmen Squared, by contrast, launches from the backdrop of air pollution, traffic noise, and

the locale which, more than any other in China, denotes and connotes public space as state power – and is, for that reason, highly surveilled. The app user, surrounded by a mass of vehicles, pedestrians, and sightseers, connects with the forbidden image of Tank Man in a move which echoes Chen Shaoxiong’s Ink History in its staging of the public secret, but heightens the sense of raw theatre through its outdoor performance, and the way it turns user into actor. The public secret as drama also plays out within the app’s visual field. The ambient streetscene is viewed in two planes on the smartphone until the Tank Man graphic – the secret – appears, sleekly contoured, pinpoint-sharp, and rendered along three axes so that its dimensionality ‘steps out’ from the rest of the pictorial field (Figure 13), chromatically and perspectivally compelling despite being invisible to all around, almost grail-like in its sudden onscreen materialization. Ultimately, the effect of Tian’anmen Squared is, once again, to combine the spectral and the comedic (or at least the playfully subversive) with this notion of digital quest.

Indeed, although 4Gentlemen call Tank Man reloaded a ‘virtual monument’, it might be truer to argue, as already suggested, that the project exemplifies Lev Manovich’s point that if the 1990s were about the virtual, ‘It is quite possible that this decade of the 2000s (and beyond) will turn out to be about the physical – that is physical space filled with electronic and visual information’ (Manovich, 2006). Taking Tank Man out of the ether and onto the street is, in this sense, entirely of a piece with other shifts in Chinese digital culture, which, as Michel Hockx has pointed out, is presently trialing the move from the World Wide Web to the freer climes of the app format. Hockx describes how online literary superstar Han Han has created a new app for accessing his work which makes use of ‘the functionalities of Internet connectivity [while] entirely bypassing the browser-based media of the World Wide Web’ (Hockx, 2015: 106).

Although Han Han has explicitly denied that his aim is to avoid censorship, the app format certainly opens up ‘new, independent avenues’ (Hockx, 2015: 107) for digital expressivity. Rendering Tank Man as an app fits neatly within this rationale, chasing down further the notion mooted in the ‘Directions to the Museum’ video: namely, that in the face of conspiracies to silence, which now focus near-obsessively on control of the internet (as shown by the Baidu search results for Tian’anmen), web-inflected physical space may emerge as an agile zone for the performance of what we might now rightly call rituals of revelation. The app, and to a lesser extent the video, are practices which allow users to embody in physical space and corporeal movement the keyboard commands of ‘find’ and ‘search’ – though the term ‘questing’ may indeed be more apposite here, since it captures better the extent to which the pursuit of Tank Man in contemporary China has an almost ceremonial character. Again, the point is not exposure, or even, necessarily, direct contestation. The quest can be justly called ritualistic or ceremonial because it is through the performance of looking – not via any object thus found, let alone exposed – that the lineaments of the public secret are held up for scrutiny.

In this sense, it is unsurprising that the underlying logic of Tian’anmen Squared reiterates the theme of inbetweenness that is immanent to both the public secret and the other artistic forms discussed here which seek to do it revelatory justice. The app is both web-driven and yet browser-free, digital and yet grounded in the materiality of the body as it moves. Above all, it exploits again and again the status of the repurposed photograph as an interstitial object. Using the app generates a complex mise-en-abîme, in which the security cameras record the user who scopes the street with his or her smartphone until the graphic of man and tank appears on screen, the vehicle’s guns trained telescopically on the user too. At this point, the user may decide, as mentioned earlier, to take a screenshot of man and tank superimposed over the streetscene. In short, the app enables no fewer than five separate camera/photographic operations, an emphatic profusion which begs its own set of questions. On one level, this is just an organic response to the memoryscape all around: just as power flows from the barrel

of a (tank) gun, to paraphrase Mao Zedong, so is history now inescapably filtered through the lens. The augmented reality app of Tank Man performs this shift repeatedly, from original photograph to computer graphic, from computer graphic back to mixed media smartphone photograph, from virtual environment to the square, and from that physical location back to the screen.

Tank Man Redux

What’s more, the app, by its very nature, is designed to rove and roam from location to location, as we see in Figure 14, which shows Tank Man in Union Square. In so doing, these iterative journeys, from square to square and beyond, seem to parlay directly with Ai Weiwei’s well-known Studies of Perspective series (Toushi yanjiu, 1993–2003), in which the artist photographs himself flicking the bird to various landmarks of authority: the White House, the Eiffel Tower, Red Square, the basilica in the Piazza San Marco, the Reichstag, the Mona Lisa (again). In naming the series as a whole Studies of Perspective, Ai Weiwei’s main point of propaganda is to make the middle finger matter more than the monument, to undermine the icons of establishment power with an equally iconic gesture of disrespect. Yet the linchpin, the coruscating core, of the series is Studies of Perspective: Tian’anmen Square, and the power of that semi-selfie snapshot, taken only six years after the crackdown, derives from its allusive and politically aggravating geometric similarity to Tank Man (Figure 15).

Ai’s insurgent middle finger, at the bottom left of the foreground, stands in for the lone protestor, while the tanks become the Gate of Heavenly Peace, adorned with Mao’s huge portrait – which has been obliterated by Ai’s finger. In both images, the stand-off occurs across the same bottom-left/top-right diagonal axis, in the midst of emptied public space. But the crushing downwards momentum of Tank Man – in which the tanks have ‘advanced across mostof the pictorial field along the lines and vectors on the street indicating the forward direction of the traffic’ (Hariman and Lucaites, 2007: 217) – is reversed as Ai’s finger protrudes as an aggressive repoussoir, taking the place of the tanks and bearing down not on the protester but on the site of state power. The planed patterning of the road markings in the original Tank Man shots, which tamely follow the convoy of vehicles, is undone in Ai’s photo, which scatters these narrow white lines across the visual field.

A Study of Perspective: Tian’anmen Square is Tank Man redux, then, with a vengeance. If so, it is ultimately predictive about the remixing of icons in digital times, and in China most particularly. Already with Ai’s photograph – a gelatin silver print, and thus an analog object par excellence – we witness a process at work that revs up noticeably under digitality. Even as echoes of Tank Man ricochet left and right across Ai’s photo, Tian’anmen Square also testifies to the partial dissolution of that source image, or rather to its capacity to absorb intrusive adaptation whilst retaining its strong recognition quotient. As an über-image, Tank Man may twist and bend, yet the centre can still hold, in much the same way that an aesthetic remediation of the black-and-white photograph of the gate at Auschwitz, emblazoned with the infamous words ‘Arbeit macht frei’, could be composed of matchsticks and still refer unmissably back to its photographic point of origin. Under digitality – within the universe of memes – remakes and remixes of photographic icons have proliferated, for the obvious reason that the speed, profusion, and plasticity of the online environment vastly multiply the opportunities for reversioning. In a non-censored web, though, these repeated remediations tend, in practice, to belong quite tightly within the same genus: they are clear scions of their photographic patriarch, as we see with ‘Syrian beach boy’, whose remakes – for all their quantity – are remarkably alike. Their purpose, after all, is in large part to keep memory refreshed, so it scarcely behooves such remediations to stray too far from the master image. This ‘family resemblance’, to borrow Wittgenstein’s term, typically breaks down when Tank Man is remediated in Chinese online spaces, for the simple reason that secrecy, not forgetfulness, is the core antagonist against which the remix is battling – and battling secrecy, as discussed earlier, requires clandestine tactics.

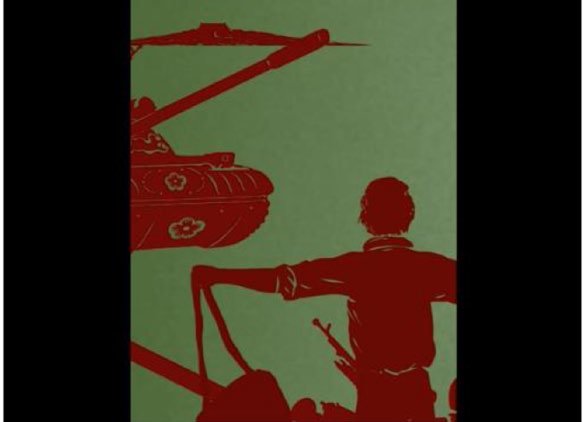

Lily and Honglei speak directly to this genealogical disintegration in a video

work about June 4th, entitled Forbidden City (Zijincheng, 2008; Figure

16), which melds digital animation with traditional Chinese paper cuts. The

piece opens with an image of an old-fashioned tea-shop window, hung

with a red paper-cut decoration of the character fu, meaning prosperity and

happiness. A flower has been cut out in each corner of the decoration, a

face-value reference to the ‘Four Gentlemen’ of Chinese artistic and botanical tradition (plum blossom, orchid, bamboo, and chrysanthemum) – and an encrypted allusion to the so-called ‘Four Gentlemen’ of the Tian’anmen Square protests: a quartet of activists, including Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, who went on hunger strike in June 1989 (and after whom the conceptual art collective are, in fact, named). As a guqin plays on the soundtrack, the paper cut disintegrates into falling petals, until only five tiny red marks remain. The camera then closes in on these shapes, revealing them to be the lone protester, three tanks, and the Forbidden City itself. For the next two minutes, the tanks and the protester – the component parts of the original Tank Man photograph – abandon their assigned places to move disjointedly and at random across the screen, until the inevitable hard collision between man and machine occurs and a spectral swirl of blood is superimposed across the visual field. It drifts like a fractal for several seconds before floating away, just as the falling petals reassemble into the character fu, the swirl of blood melts into steam from a teacup, and the scene returns to the tea shop as if the bloodshed had never happened. Narratively, the animation rehearses he same interplay between spectrality and ‘see no evil’ which I have traced throughout this article, at the time as metaphorizing the idea that China’s rise since the 1990s is predicated on precisely this silent collusion with a violent order – or, as Jiang Zemin put it in his famous motto for the post-Tian’anmen era, ‘Keep your mouth shut and get rich’ (mensheng fadacai). Meanwhile on the meta-plane, via its dismemberment of the Tank Man photograph, the video acts out the process of reductionist redux, the stripping down to barest bones that icons must undergo if they are to maintain some kind of visibility in suppressive environments.